What are the psychological consequences of working in this field for women survivors of abuse?

Women’s community groups as well as domestic and sexual abuse support organisations provide safe spaces of healing for women surviving trauma and abuse; spaces where mutual understanding and shared experience can offer a sense of hope and recovery. It is quite usual for a significant proportion of support workers and practitioners within these organisations to share lived experiences of abuse, estimated to constitute over 50% of organisational staffing (Slattery and Goodman, 2009; Bemiller and Williams, 2011). This has been common since the first women’s groups were formed in communities in the 1960s and 1970s in England and these women’s community services are arguably never more needed than currently, given the current epidemic of violence against women and girls being perpetrated (Justice Inspectorates, 2021).

However, what of the impact on support workers with lived experience of abuse? I interviewed twelve women support workers from five different women’s support organisations to ask about their thoughts, feelings, and experiences regarding their career choice and to enquire how this had affected them in terms of both positive and negative emotional impacts. What were they gaining personally and what was the impact on them when undertaking this emotionally challenging work?

Creating something positive from lived experience of abuse

The findings from my study (Gilbert, 2020), found that the experience was distinctly personal to each woman I interviewed, as was the readiness to feel able to work in women’s support work. Overwhelmingly, a key benefit for interviewees was the notion of purpose. For women survivors who chose to work in domestic abuse support work, this practice role could be the mechanism for many to achieve a personal sense of purpose and to make sense of a traumatic period in their own lives, using the experience in a positive way. One woman spoke about this in detail to me and said,

“I suppose it’s a silver thread that can be pulled from the trauma of what I went through. I can pull one positive aspect from the experience of abuse and use it for something good, something honourable – helping other women to move from victim to survivor, like I was able to, with the help of other women survivors. “

In addition to purpose and meaning, women spoke of the rise in their own self-esteem and their feelings of a sense of belonging to something important. In being able to work as a professional in domestic/sexual abuse support work, this enabled survivors to rebuild their sense of confidence and created a sense of empowerment by enabling them to create a professional life after experiencing abuse themselves. Women interviewed identified an environment of shared understanding, a sense of feeling comfortable, and to have had a sense of a unique connection with their women service users. The notion of having ‘walked in the same shoes’, enabled survivor support workers to feel able to provide what they described as an authenticity of support to other women experiencing abuse and violence. They strongly believed that in offering what could be termed ‘peer’ support, this felt very different to support from someone without similar shared lived experience.

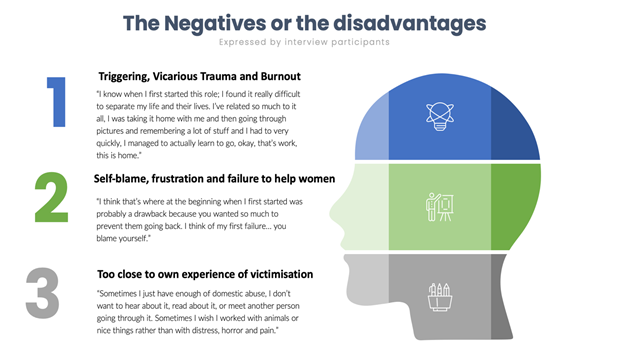

Personal costs of survivor support work

Conversely, there were personal costs to being involved in support work as a survivor. The main issue appeared to be triggering painful memories and trauma, irrespective of the time between experience and practice. Some women survivors found it difficult not to recall events in their own lived experience when working with women service users, especially if their personal accounts resonated with their own experiences. Vicarious trauma is a potential risk for all support workers of victims of domestic abuse, so, too, burnout or countertransference (Iliffe and Steed, 2000).

The protective factor to mitigate against risk was supportive supervision from a line manager or a clinical colleague, and from this small-scale study, for many of these practitioners, this was not provided and did not meet their needs as survivors support workers. The further saturation of hearing about domestic abuse and in hearing the distress of service users over and above the survivor’s own lived experience is likely to be damaging without such clinical support.

Summary

The benefits to both survivor support work and to the women service user can be powerful within the domestic violence and women’s support sector. Survivor support workers can gain a sense of self- actualisation, esteem and belonging when working in their practitioner roles.

However, there can be a risk of re-victimisation to the support worker, particularly where appropriate clinical supervisory support is not provided. In using their own lived experience as a source of knowledge, a survivor support worker can enhance her own sense of self-worth, using her experience positively to add to her own process of recovery and self-actualisation.

There is a wealth of specialist women’s community support knowledge in the UK, including grassroots organisations formed by and for survivors themselves. Many of these are outside of the main large charity organisational funding steams and they struggle to maintain their services in the face of increasing demand and short-term funding arrangements. The whole domestic abuse support sector needs longer term, ringfenced funding for specialist domestic abuse support organisations (SafeLives, 2021), especially those who provide for disadvantaged groups, those with complex disadvantage or those serving (semi) rural areas. This will then enable all survivor support workers to access the appropriate level of clinical or support supervision that they need to remain safe whilst undertaking this challenging but essential service in our community.

This blog post is based on a presentation delivered by Beverley Gilbert, Senior Lecturer, University of Worcester at the 4th European Conference on Domestic Violence on 15th September 2021, held online from Slovenia.

Beverley Gilbert

Beverley is a Senior Lecturer in Violence Prevention and Criminology at the University of Worcester. Her academic career follows 30 years working in various roles within the criminal justice sector. Her PhD research with Anglia Ruskin University examines peer mentoring with women who have multiple and complex disadvantages. Beverley is a member of the Trauma and Violence Prevention research theme at the University of Worcester, she is an Independent Member of Women Against Violence in Europe (WAVE) and Associate Member of Work with Perpetrators – European Network (WWP-EN).